Ella Wilkinson

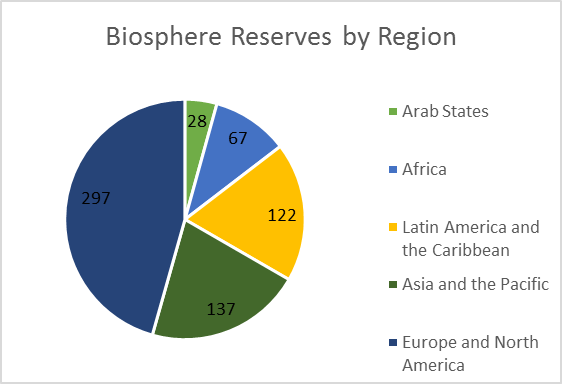

“There are currently 651 biosphere reserves in 120 countries, including 15 transboundary sites. The total surface of biosphere reserves worldwide covers 616,708,840.23 hectares.” (4th World Congress Of Biosphere Reserves[b], 2015). In addition, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation’s Man and Biosphere Programme is one of the most high profile international conservation instruments globally.

Key words: Environmental governance, UNESCO, Man and Biosphere Programme, United Nations, Biosphere Reserves, genetic diversity, natural resources, ecosystems, man-in approach, sustainability, international co-operation, zonation

REPORT

The Man and Biosphere Programme (MAB) began in 1968 with the UNESCO Biosphere Conference which included non-governmental organisations along with government representatives in response to perceived biosphere threats by UN Member States. To reverse this trend of loss and degradation, and with a particular emphasis on preserving “genetic resources” (George Wright Society, 2006) and “life-support potential” (Fletcher, 1997 p. 2), an International Coordinating Council was created and had its first session in 1971. MAB was formally endorsed at the UN Conference on the Environment in 1972, with the aim of protecting areas representing the “main ecosystems of the planet” (George Wright Society, 2006) and an understanding that the formation of such “biosphere reserves” was to meet educational, cultural, scientific as well as recreational needs (George Wright Society, 2006).

Though subject to some skepticism (Harman, 2015), Agenda 21 – a product of the 1992 Convention on Environment & Development in Rio de Janeiro – reinforced the importance of MAB, and it’s Biosphere Reserves (Berce-Branko, 1997), specifically in Section II: Conservation and Management of Resources for Development. This includes combating deforestation, protecting fragile environments, conservation of biological diversity and the control of pollution, amongst others (United Nations, 1992).

UNESCO does not directly fund its World Heritage Sites (which includes Biosphere Reserves) and “Biosphere Reserve recognition does not convey any control or jurisdiction over such sites to the United Nations or to any other entity” (Fletcher, 1997 p. 1) – so they remain the responsibility and property of the host country(s). Areas are only considered for Biosphere Reserve status at the request of the host country and, similarly, will be stripped of such recognition if requested by the countries government (Fletcher, 1997). Therefore, the benefits of seeking Biosphere Reserve status link largely with advice in brokering projects or setting up “durable financial mechanisms” (UNESCO, 2005 p. 4) for the Reserve to be self-sustaining and of economic benefit to the host country (UNESCO, 2005).

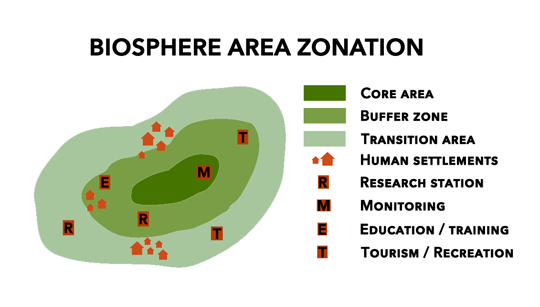

In developed countries, Biosphere Reserves have often been “superimposed” (Agardy, 1993 p. 76) on an existing, protected National Park (or similar) designated area. However, in developing countries Biosphere Reserves have often needed to be created from “scratch” (George Wright Society, 2006) – largely these follow a design popularised by the Biosphere Reserve Programme. Integrating a “Core Area” (very limited human activity and development), “Buffer Zone” (increased but still limited and monitored human activity and development. The area where activities compatible with the core area may take place e.g. education, research and low-impact leisure) and the “Transitional Area” (where industries and settlements are permitted to exist, provided they minimise their impacts on the Core Area) (George Wright Society, 2006) (Batisse, 2007) (UNESCO, 2016[a]). After 1974, when a dedicated Task Force drew up a set of objectives and characteristics for Biosphere Reserves which covered a wide variety of criteria but gave no hierarchy and provided no priorities for selection, more developing countries began to come forward with suggestions for their own, usually zonated, Biosphere Reserves (Batisse, 2007). The Zoning Technique has been adopted in many other land-use strategies, environmental and otherwise (notably in UNESCO World Heritage Sites across the globe, though in many cases World Heritage Properties are already embedded in Biosphere Reserves (Engels, 2015)) such as the Monarch Butterfly Reserve in Mexico (UNESCO, 2007), where inscription led to a bold collaborative action plan between Mexico, Canada and the USA (Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 2008).

View presentation (PDF):

Man and Biosphere Programme (MAB) Ella Wilkinson

Works Cited:

- 4th World Congress Of Biosphere Reserves (2015[a]). 4th World Congress Of Biosphere Reserves Lima, Peru from March 14-17 in 2016. [Online]

Available at: http://www.ivcongresomundialreservabiosfera.pe/index.php/en/

[Accessed 13 February 2016]. - 4th World Congress Of Biosphere Reserves (2015[b]). Statistics of Biosphere Reserves. [Online]

Available at: http://www.ivcongresomundialreservabiosfera.pe/index.php/en/reservas-de-biosfera/estadisticas-sobre-reservas-de-biosfera

[Accessed 13 February 2016]. - AfriMAB Network (2010). African Biosphere Reserves Network AfriMAB Charter, Nairobi: UNESCO Man and Bipsphere Programme.

- Agardy, T. (1993). Draft Guidelines for Biosphere Reserve Planning. In: A. Price & S. Humphrey, eds. Application of the biosphere reserve concept to coastal marine areas: papers presented at the Unesco/IUCN San Francisco Workshop of 14-20 August 1989 . s.l.:IUCN, Marine Conservation Programme, pp. 75-88.

- Batisse, M. (2007). Developing and Focusing the Biosphere Reserve Concept. In: B. Thakur, ed. Perspectives in resource management in developing countries, Volume 2, Part 1. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, pp. 160-177.

- Berce-Branko, B. (1997). Bioregional Management And Local Agenda 21 A Viable Solution To Environmental Problems. In: M. Vezjak, E. A. Stuhler & M. Mulej, eds. Environmental Problem Solving From Cases and Experiements to Concepts, Knowledge, Tools and Motivation: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Case Method Research and Case Method Application. Munich and Mering: Rainer Hampp Verlag, pp. 17-20.

- Commission for Environmental Cooperation (2008). North American Monarch Conservation Plan, Montréal: Commission for Environmental Cooperation.

- Engels, B. (2015). Natural Heritage and Sustainable Development – A Realistic Option or Wishful Thinking? In: M. Albert, ed. Perceptions of Sustainability in Heritage Studies (Volume 4). Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 49-58.

- Fletcher, S. R. (1997). CRS Report for Congress, Biosphere Reserves: Fact Sheet, Washington DC: Congressional Research Service: The Library of Congress.

- George Wright Society (2006). The UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Program: What’s It All About?. [Online]

Available at: http://www.georgewright.org/mab.html#Anchor-Why-11481

[Accessed 13 February 2016]. - Gilbert, V. T. (2014). Biosphere Reserves: A New Look at Relevance to Meet Today’s Challenges. In: S. Weber, ed. Protected Areas in a Changing World: Proceedings of the 2013 George Wright Society Conference on Parks, Protected Areas, and Cultural Sites. Hancock: George Wright Society, pp. 31-34.

- Harman, G. (2015). Agenda 21: a conspiracy theory puts sustainability in the crosshairs. The Guardian, pp. http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/jun/24/agenda-21-conspiracy-theory-sustainability.

- Nedre Dalälvens Intresseförening (2016). [Online] Available at: http://www.nedredalalven.se/index.php/en/biosphere [Accessed 13 February 2016]

- Netherlands National Commission for UNESCO (2014). Nationale UNESCO Commissie; Man and Biosphere: will the Netherlands become more active?. [Online]

Available at: https://www.unesco.nl/en/node/2683

[Accessed 19 February 2016]. - Stevens, G. (2011). Save Our Seas Foundation; Baa Atoll, Maldives – A UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve. [Online]

Available at: http://saveourseas.com/update/baa-atoll-maldives-a-unesco-world-biosphere-reserve/

[Accessed 19 February 2016]. - UNESCO (2005). Biosphere Reserves Benefits and Opportunities, Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO (2007). Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve World Heritage Site Nomination Document, Mexico: UNESCO.

- UNESCO (2016[a]). Zoning Schemes. [Online]

Available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/main-characteristics/zoning-schemes/

[Accessed 13 February 2016]. - UNESCO (2016[b]). MAB Networks. [Online]

Available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/man-and-biosphere-programme/networks/

[Accessed 28 February 2016]. - UNESCO (2016[c]). Urban Systems. [Online]

Available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/specific-ecosystems/urban-systems/

[Accessed 28 February 2016]. - United Nations (1992). United Nations Conference on Environment & Development Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992 , Rio de Janerio: United Nations.